Dortmund, 12th January 2024

Darleen Hüser is one of the ISAS researchers who are carrying out research as part of Transregio 332. The neutrophils and imaging techniques encountered in this project were entirely new to the 28-year-old when she first began working on it. In this interview, the biologist tells us why she expects to come up against hard work in uncharted territory.

Darleen Hüser performs scientific work in the Bioimaging research group. Her PhD topic relates to neutrophil granulocyte immune cells.

© ISAS / Hannes Woidich

What are your tasks as a doctoral candidate in Transregio 332?

Hüser: It is known that neutrophils differ in rheumatoid arthritis depending on their location in the knee joint, whether they are in the synovial cavity or the synovial fat pad, for example. However, the composition of these sub-populations of neutrophils – i.e. what the immune cell fingerprint looks like in rheumatoid arthritis – is still unclear. I am testing the hypothesis that the various neutrophil sub-types trigger different inflammatory responses in the macrophages.

This information might be of great importance for a future targeted treatment of the illness. The objective is to find out how many neutrophil sub-types there are, exactly which sub-populations the entire neutrophil infiltrate is composed of and precisely where the individual sub-types act in the inflamed joint. For this purpose, I am using various imaging technologies, such as Confocal Microscopy and Light Sheet Fluorescence Microscopy, to examine the knee joints of mice with rheumatoid arthritis.

Why are you carrying out some of your research using the confocal microscope?

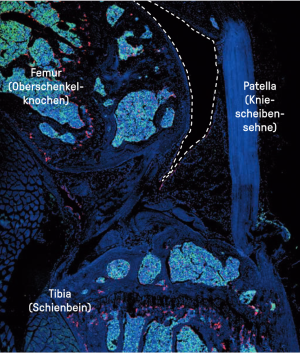

Hüser: We would like to find out how the neutrophil sub-types that have migrated into the synovial cavity differ from those in the synovial fat tissue of the knee joint. This spatial information is crucial in answering our questions. We want to use this information to learn the reason for the different infiltration profiles. After I have examined the knee joint under the light sheet fluorescence microscope, I prepare it for further analysis under the confocal microscope. The latter features a very high resolution at the sub-cellular level and provides two advantages: firstly, I am able to identify which neutrophil sub-types are present in which anatomical niche. Secondly, confocal microscopy enables me to perform an analysis of cell-cell interactions between the various neutrophils and the macrophages located in the tissue.

The dashed lines surround one part of the synovial cavity – dark area – between the femur (thigh bone) and the synovial fat tissue/synovial soft tissue below the patellar tendon (kneecap tendon) in a healthy mouse. Synovial cavity is the name of the joint cavity that is lined by a thin layer of the synovial membrane. The cells stained red are the macrophages. In a healthy knee, a special macrophage population, the synovial lining macrophages, form a barrier along the synovial membrane. The cells marked in green are the neutrophils. The image taken using a confocal microscope shows that, in a healthy state, no immune cells can be seen in the synovial cavity.

© ISAS / Darleen Hüser (Bioimaging)

What challenges do you face in this research project?

Hüser: The mix of imaging methods is very exciting, but at the same time my research is hard work. For light sheet fluorescence microscopy, I need the knee joint to be a transparent intact joint. This means I first deal with clearing (see info box) the bones. I subsequently reverse this step and then manually cut the joint for confocal microscopy into thin slices of between ten and 14 micrometres on the cryostat microtome. What sounds easy in theory is tricky in the laboratory. Firstly, because there are only a few established methods of performing microscopic analyses on bones, so I first had to develop a suitable protocol for the treatment of the joints. Secondly, I require even and consistent cuts – which presents a challenge when it comes to cutting a knee joint comprised of bone, soft synovial tissue, tendons and fat pads. I have to work with a razor-sharp tool and apply exactly the right amount of pressure to the blade so that the cuts are accurate and there are no bone fragments. The morphology, meaning shape and structure, of the tissue should be maintained to the greatest possible extent.

CLEARING

As tissue and bone can absorb, reflect or scatter light, they need to be chemically treated to see deep inside them beyond the surface. The clearing method developed for this purpose by Prof Dr Anika Grüneboom is used in light sheet fluorescence microscopy at ISAS and worldwide. With this method, researchers use cinnamic acid ethyl ester, a natural flavouring, to make the samples transparent. Grüneboom’s clearing can be reversed, meaning that no samples are destroyed and the same bones or the same tissue can be subsequently examined under the confocal microscope, for example.

Is there one aspect of your work that you find especially satisfying?

Hüser: It was not until the project began that I started to become aware of how extensive and heterogeneous the world of neutrophils is and how important they are for our immune system in so many ways. But most of all: there is so much we have no idea about when it comes to neutrophils. Apart from plunging into a new thematic area, when I first started working on the project most of the imaging methods were new to me too. I find it fascinating what information we can gather from a knee joint with the help of a mix of imaging procedures and which details suddenly become visible when doing so.

(The interview was conducted by Sara Rebein.)

"TRR 332 – Neutrophil Granulocytes: Development, Behaviour & Function" is funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) – project number 449437943.