Dortmund, 8th July 2025

Cardiac insufficiency (Heart failure) is one of the most common chronic diseases in Germany, affecting around four million people. In general practice, barely a day goes by for doctors without patients presenting with the symptoms of heart failure and the complications and treatment challenges that come with this disease. In recent years we have seen an arsenal of drugs being developed to combat it, including ACE inhibitors, beta blockers, SGLT2 inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs). However, the clinical reality is that many patients also have additional disorders, especially chronic kidney disease (CKD), which makes using these drugs more difficult or in some cases even impossible. ISAS researchers are therefore focussing on broadening the range of treatments for heart failure specifically.

Heart failure is one of the leading causes of death in Germany. Doctors distinguish between two main forms. In systolic heart failure, the heart muscle is no longer strong enough to pump enough blood into the circulatory system. In the other form, diastolic heart failure, the organ pumps as usual, but the heart has become stiff or thickened and, as a result, does not fill sufficiently with blood. This also leads to less blood than necessary entering the circulatory system. People affected by both types often feel short of breath and weak. Fluid often accumulates in their lungs, arms and legs. Cardiac arrhythmias can also occur.

A multi-organ vicious circle

However, it is rare for patients to suffer from heart failure alone. Most of those affected also have other chronic disorders. Around half of all people with heart failure also have CKD. This often means that the kidneys are less effective at removing toxins and fluid from the body. In combination with heart failure, this creates a vicious circle: because the weakened heart is pumping less blood, blood flow to the kidneys is reduced, which further impairs how they work. This results in fluid and harmful metabolic products accumulating in the tissue, which in turn puts additional strain on the heart. “CKD patients have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including structural heart disease, heart failure and sudden cardiac arrest,” write Prof. Dr Kristina Lorenz, Head of the Cardiovascular Pharmacology research group at ISAS, and general practitioner (GP) Dr Jonas Knaup in an article published in 2024 in the journal MMW – Fortschritte der Medizin.

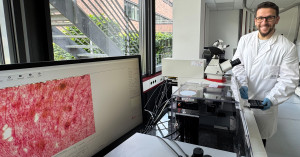

Prof. Dr Kristina Lorenz heads the Cardiovascular Pharmacology research group and the Translational Research department at ISAS. She is also Head of the Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg.

© ISAS / Hannes Woidich

Article Recommendation

Lorenz, K., Knaup, J.

(2024) Nach Krankenhausaufenthalt: Wie die Behandlung weiterführen? MMW – Fortschritte der Medizin, 166, 44–47.

Treatment plan pillars on shaky ground

When treating heart failure, doctors currently rely on a “four-pillar therapeutic approach” consisting of various medications: ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors, beta blockers, MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors. The last of these is the only class of active substances that has proven to be effective against both systolic and diastolic heart failure.

Ideally, these four pillars are used simultaneously to not only alleviate the symptoms of heart failure, but also to slow the progression of the disease. However, in patients with comorbidities – CKD in particular – this treatment plan quickly falls apart if the weakened kidneys are overloaded and can no longer effectively flush the active substances out of the body. “Sometimes one pillar falls, sometimes three,” reports Knaup from his everyday practice.

In some cases, the only remaining option for multimorbid patients is to combat the symptoms with diuretics, i.e. medications that increase urine production. These at least reduce the accumulation of fluid in the body that is typical of heart failure. However, in advanced kidney failure, even this strategy eventually reaches its limits. “The balancing act becomes ever more difficult,” says Knaup. For GPs like him, there is long-term hope on the horizon at ISAS, where pharmacologist Lorenz and her team are currently working on several promising new medicinal approaches.

Dr Jonas Knaup is a specialist in general practice at the Burgbernheim Medical Care Centre.

© Privat

A stress-resistant heart thanks to proteins?

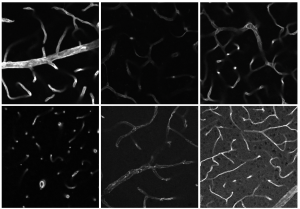

For a start, researchers at ISAS are developing strategies to combat the pathological remodelling processes in the heart muscle associated with heart failure. When the strength of the heartbeat drops, so too does the blood supply to the organs, causing the body to release stress hormones. These cause the heart to beat faster and harder. In the short term, this actually boosts physical performance – which in the past helped humans evolve to run away from acute dangers, such as a bear on the attack. In the long term, however, these stress hormones bring about changes in the heart by stimulating the growth of heart cells and connective tissue. This ultimately makes the heart thicker and stiffer – and even less able to pump blood.

Lorenz's Cardiovascular Pharmacology research group has identified various proteins that counteract this dynamic. “These include a peptide agent that acts directly on the signalling pathway that inhibits pathological heart growth. This enables us to stop this development,” says the researcher. A second protein, in turn, appears to be able to increase the beat strength of the weakened heart muscles without the mechanism of heart growth, which is so dangerous in the long term, even starting. A third protein, the investigation of which is still in the early stages, appears to have the potential to improve the elasticity of the heart muscle and to do so in both systolic and diastolic heart failure.

New therapy pillars for a broader range of treatment options

If the identified molecular points of attack prove effective and new drugs can be developed from them, they would significantly expand the existing arsenal of available treatments. “These would be entirely new pillars of therapy,” explains Lorenz. In other words, the proteins that the ISAS team is working on are not simply variants of the four existing approaches to treatment, but active principles used to treat heart failure through novel mechanisms that have not yet been deployed.

GP Knaup would welcome these additional treatment options. He sees heart failure patients in his practice almost every day, whose comorbidities often make treating them a challenge. “You just try to somehow hold the rickety system together,” says the doctor. In view of the prevailing demographic trend, physicians must prepare to be confronted with this problem even more frequently in the future. The number of people affected is rising, says Knaup. He goes on: "The older the population gets, the more common this disease becomes.”

(Ute Eberle)