Dortmund, 7th October 2022

Scientists have a variety of modern analytical methods at their disposal for analysing substances and identifying unknown constituents. This includes ion mobility spectrometry. Researchers at ISAS succeeded in producing a fully functional ion mobility spectrometer (IMS) using 3D printing for the first time in 2021. They published their results in the renowned journal Materials Today. Now Dr Sebastian Brandt, a physicist and the corresponding author of the publication, answers questions about the advantages and background of the development.

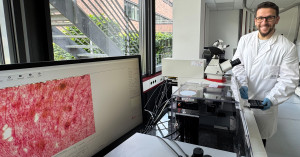

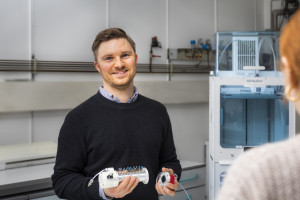

Dr Sebastian Brandt showing the first IMS from the 3D printer in the lab.

© ISAS

An IMS can be used to characterise charged, gaseous molecules based on their individual velocities in an electric field. Compared to other analytical methods, ion mobility spectrometry features high sensitivity and short measuring times with a low instrumentation requirement. It detects individual analyte molecules in ten billion gas molecules with a measurement duration of less than one second.

How did the idea to produce an IMS exclusively using 3D printers come about?

Brandt: Our Miniaturisation research group has been toying with the idea of printing a complex technical device using our 3D printers for some time. The idea for printing the entire IMS came to us at some point, as we had already printed small individual parts to customise conventional IMS according to our needs. However, these subsequent changes are difficult and time-consuming, just like the construction of an entire IMS itself. Here at ISAS, both are usually done by the workshop, which has to make a new sketch for each new model. That’s why we initially only wanted to use the 3D printer to produce and optimise a prototype, which would facilitate subsequent production by our colleagues in the workshop. But that worked out so well, that we worked intensively on taking it beyond that point.

What is the advantage of an IMS from the 3D printer?

Brandt: A significant advantage is definitely the low material consumption. As a rule, an IMS is manufactured subtractively. That means that you start out with a block of material and remove some of it until you have the desired shape. The rest ends up in the trash. In contrast, the 3D printing process is quick and additive. With the 3D IMS, we only consume the material that we actually need. This makes the 3D printed IMS cheaper, faster and more environmentally friendly overall than a conventionally produced IMS. Compared to the subtractive manufacturing method, we can now almost halve the production time with 3D IMS. The costs of the materials also drops to a quarter. And current developments show that it is possible to optimise the IMS for an even shorter printing time. In addition, the 3D printer works almost completely autonomously. Only a small amount of post-processing by humans is needed, so we can also significantly reduce the operator’s working time.

Another point in its favour is flexibility. We have built in a magnetic click system into our 3D IMS, so we can change the parts very easily using modules. For example, not only can we quickly vary the Bradbury Nielsen Gate or the length of the drift tube depending on the sample or analyte by means of 3D printing, but also only have to shut the device down for a short time to replace it. This allows us to study samples of various textures including both liquid samples, such as blood or urine, and gaseous samples, such as breath. It also makes it easy for us to try out new modules. The path from the idea to the application is thus shortened many times over and is considerably less expensive.

Article Recommendation

Drees C, Höving S, Vautz W, Franzke J, Brandt S. 3D-printing of a complete modular ion mobility spectrometer. Materials Today, Vol. 44, S. 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2020.10.033

What is a 3D IMS suitable for?

Brandt: In the past, the handy IMS were used almost exclusively for detecting drugs or hazardous substances. However, they are now also attracting interest in biomedical and forensic research. Doctors can use them, for example, to test patients’ breath for certain bacterial or viral pathogens, such as in pneumonia. The IMS can also detect drugs, such as the anaesthetic propofol, in exhaled air, making it easier to monitor anaesthesia. Despite the versatility of its application possibilities, however, an IMS is not yet a technology suitable for mass production. The initial costs for a simple 3D printer are lower, given the production time and costs, and its handling can be quickly learned.

What role do other measuring instruments from the 3D printer play?

Brandt: I see the future of analytics in the use of additive manufacturing methods like 3D printing; at least I dream about it. However, I am also realistic and aware of its current limitations. One current hurdle, for example, is the right materials. Most commercially available 3D printing materials are designed to look good and have a nice colour, for example. Optics are not important to us in analytics; we need the material to be highly durable and compatible with the chemicals used. That’s why our research group is currently working on our own materials that meet our requirements for measuring instruments from the 3D printer.

(The interview was conducted by Cheyenne Peters.)