Dortmund, 8th May 2024

For half a day at Girls' Day 2024, twelve schoolgirls were able to find out in their own experiments how bacteria can be hunted down and kept in check, why organs become transparent with the help of cinnamic acid ethyl ester, and what can be seen under the microscope during a heart attack.

Together with PhD students Antonia Fecke and Luisa Speicher, who accompanied the event as scientific guides, the seventh to ninth graders gained practical insights into the immune system – and learned a lot about bacterial and sterile inflammation. Under the guidance of Dr Christina Sengstock and Dr Christiane Stiller, the pupils learned how to multiply bacterial cultures in the laboratory. They also investigated the effect of silver acetate on Escherichia coli. With Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom and Luisa Röbisch, everything revolved around the light sheet fluorescence microscope. Before they treated organs with cinnamic acid ethyl ester – a component of cinnamon flavour – and analysed pre-treated samples, the participants had conducted an experiment with glass beads to gain a better understanding of the procedure for optical clearing.

The Communications team coordinated the Girls' Day project at ISAS in 2024, and this time received active support with the organisation and implementation from intern Clara Manthey (student at TU Dortmund University). In the run-up to the event, Luisa Becher, also a student at TU Dortmund University, had already played a key role in the conception and preparation.

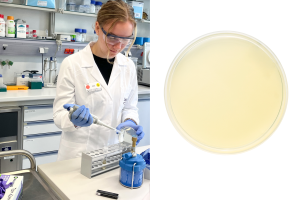

In the bacteria lab, Jule (13) is practising how to use a pipette. The work is taking place next to a Bunsen burner the whole time. It forms a sterile circle around its flame, in which it is possible to work in a sterile environment. Within this sterile zone, Jule is training how to pipette, first with water and then with a prepared Luria-Bertani medium. The latter is a nutrient medium for cultivating bacteria. For this, the 8th grader has already placed a new sterile plastic tip onto the pipette before she applies the medium to the prepared agar plate. The aim of this experiment is for Jule and the other pupils to learn how to handle bacterial cultures (E. coli) and how to multiply them to continue working with them afterwards.

© ISAS (links) istockphoto/grebcha (rechts)

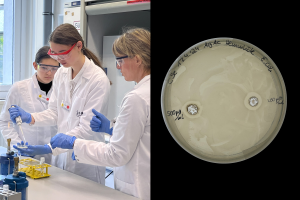

Once the students have familiarised themselves with pipetting, they move on to the "inhibition zone experiment". Dr Christina Sengstock (on the right in the picture) is standing by to help them. Sara (14, photo: centre) has already labelled the Petri dish with the culture medium. She is now holding an agar plate and a pipette in her hands. She uses the pipette to drip Luria-Bertani medium onto the plate. The student makes sure that she uses the exact amount of liquid required. The girls have previously taken the liquid from a test tube using the pipette. They will then spread the medium on the plate by spreading it out with a glass spatula they had bent themselves. Sophie (13) is watching attentively before pipetting herself next. The whole exercise serves as preparation for the following experiment. For this, the pupils will make holes into the agar on the plate. They will then pipette silver acetate into the punched-out area. Agar plates with E. coli-cultures are used in real daily life in the laboratories. The silver ions have an antimicrobial effect – they inhibit the growth of bacteria. That is why inhibition zones around the area treated with silver acetate can later be seen with the bare eye.

© ISAS

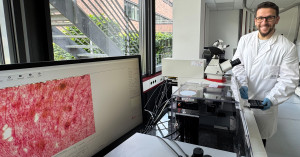

The young researchers have moved from the bacteria lab to one of the microscopy labs. To understand how organs become transparent for the analysis under the light sheet fluorescence microscope, the students have been given cups with glass pearls. They are part of an experiment conducted by Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom and Luisa Röbisch. The two have chosen this experiment to illustrate the principle of optical clearing. What Sophie (left) and Sara cannot see at first because the glass beads do not let any light through, and the beaker appears opaque: There are small red plastic hearts between the glass beads. The pupils are slowly pouring cooking oil into the beaker. The oil displaces the air between the glass beads. The similar refractive index of glass and oil ensures that the hearts in the beakers become visible.

© ISAS

Sara (right) and Sophie are working with organ samples. They are carefully preparing the delicate samples for later use under the light sheet fluorescence microscope. They are using tweezers to pick up the hearts and thymus glands of mice, and take them out of an ethanol solution. Prof Dr Anika Grüneboom and Luisa Röbisch have prepared samples of the heart, bowel, and thymus for the experiment in advance and placed them in an ethanol solution. This alcohol solution is used to dehydrate the samples. The students are carefully placing the samples in small containers filled with ethyl cinnamate before they will seal the jar. The cinnamic acid ethyl ester is part of Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom patented clearing process. (Editor's note: The samples were already available; no organ removals were carried out for the event).

© ISAS

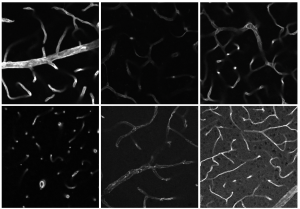

Jule (left) is taking a close look at the bowel. She can already see that it is transparent. The lab is darkened with roller blinds because the students will next go to the lightsheet fluorescence microscope. Because clearing some of the organs takes several days, biotechnologist Luisa Röbisch had prepared some samples for Girls' Day a few days before the event. Immunologist Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom will later place a transparent heart under the light sheet microscope. The device fans out the dot-shaped laser beam like a sheet of paper. The thin sheet of light created in this way illuminates each individual layer of the sample. Because the samples are transparent, the laser can penetrate them almost unhindered – and take an image of each layer. At Girls' Day, Grüneboom will later discuss the individual images of a heart after a heart attack with the students. And she will then assemble these images into a 3D model on the computer. (Editor's note: The samples were already available; no organ removals were carried out for the event).

© ISAS

The last part of the programme is about how pathogens – in this case E. coli bacteria – multiply and look on the agar plates after a few days. Another topic: immune cells such as macrophages which exaggerate with "cleaning up" after a heart attack and therefore damage the body (sterile inflammation). At this part of the Girls’ Day, the researchers have also shown images that they had taken under a confocal microscope. They revealed a section of the heart tissue with an accumulation of macrophages. Afterwards, Dr Christiane Stiller (from left to right), Luisa Röbisch and Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom are answering the students’ questions about their day-to-day work at ISAS.

© ISAS

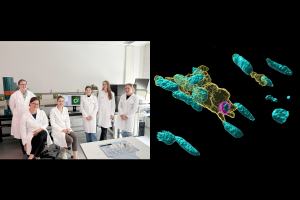

So many bright and curious minds took part in the Girls' Day event at ISAS. At the end of the day, the twelve students gave positive feedback on the day at the institute. And who knows, maybe the photo also shows the next generation of women in research? In any case, the motto "I love science" applies to all those present. Luisa Röbisch, Prof. Dr Anika Grüneboom, Dr Christiane Stiller, Cheyenne Peters (Communications team), Clara Manthey (intern in the Communications team), Luisa Speicher and Antonia Fecke (from left to right) also had a lot of fun carrying out the experiments and presenting their work. (Editor's note: Dr Christina Sengstock and Sara Rebein are missing from the photo).

© ISAS