Dortmund, 30th January 2026

Felix Hormann is a doctoral candidate in the Lipidomics research group at ISAS, and he conducts research on the spatial quantification of lipids. Since November 2025, he has been in Copenhagen for a three-month research stay. In this interview, the 27-year-old chemist talks about his experiences at the University of Copenhagen and shares his impressions of life inside and outside the laboratory.

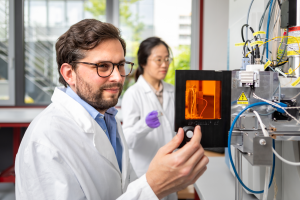

ISAS doctoral researcher Felix Hormann (27) is undertaking a three-month research stay at the University of Copenhagen. In this interview, he shares his experiences from the Danish capital.

© Privat

Why did you decide to undertake a research stay in Copenhagen?

Hormann: Originally, I wanted to spend a semester abroad during my master's studies, but unfortunately that coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s important to me to experience other working cultures and to live outside Germany for a while. From a professional perspective, the prospect of receiving valuable feedback to complement my research at ISAS with Prof. Dr Sven Heiles was decisive. Prof. Dr Christian Janfelt's research group here in Copenhagen can offer me insights that are not available in this form in Germany. I am currently working at the Department of Pharmacy at the University of Copenhagen, where the focus is on analysing drugs, their interactions, and their distribution within tissue. Various mass spectrometry imaging methods are employed, similar to those we use in Dortmund. Therefore, the methods I’m learning here can easily be transferred to our target molecules, such as lipids and metabolites, which we are investigating in Dortmund.

What do you think of the Danish capital so far?

Hormann: I really like Copenhagen. The city is very bicycle-friendly, and you can get almost anywhere by bike. At first, it was a new experience to find myself in a real bicycle traffic jam in the mornings, together with so many other people, in front of the university. Of course, there are traffic rules, but you also have to go with the flow a bit. Copenhagen is especially beautiful during the Christmas season. There are many Christmas markets offering gløgg and ice rinks for skating. The harbour is filled with illuminated canoes during the Santa Lucia Festival of Lights. And, of course, there’s the traditional julefrokost in the research groups – Christmas parties that already begin at lunchtime and go on well into the evening. However, I was repeatedly told that I should definitely come back in the summer, when Copenhagen is said to be even more beautiful.

What are you researching during your time in Copenhagen?

Hormann: In general, it involves the spatial quantification of analytes within a tissue, that means determining the absolute concentration of a substance in specific areas – for instance, in the brain. Unlike my work at ISAS, which focuses on measuring lipids, Prof. Dr Janfelt's research group examines the distribution of drugs in the body. The spatial quantification of these molecules is somewhat easier as it involves the targeted analysis of a few defined molecules. My long-term research goal in Germany is to use these experiments as a basis for quantifying large numbers of lipids with spatial resolution. In Copenhagen, I’m learning the most important basics for this purpose, so that I can then improve our measurement strategies at ISAS in the Lipidomics research group.

What does your day-to-day work as a visiting scientist involve?

Hormann: I’ve access to several mass spectrometry imaging systems that use different approaches to ionisation and imaging. My work involves characterising the performance parameters of these technologies. We compare them with each other to determine which methods are most effective for which molecules. Sensitivity plays a major role here, that is how reliably very small quantities can be measured.

Until now, I’ve worked with mass spectrometry imaging using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation, or MALDI for short. In this process, the molecules are ionised using a laser and an auxiliary substance called a matrix which is then analysed using a mass spectrometer. In Copenhagen, I’ve also received training in desorption electrospray ionisation, or DESI for short. With this technique, ionisation is carried out using a fine solvent spray. I also spend a large part of my time optimising various sample preparation steps so that they can be applied in Dortmund later on.

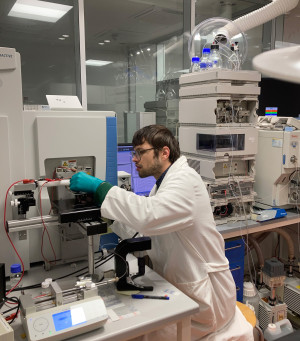

Felix Hormann (pictured here at the mass spectrometer) spends several hours a day working in Prof. Dr Christian Janfelt's laboratory – until the obligatory coffee break with his Danish colleagues.

© Privat

In Copenhagen, the chemist often travels by bicycle.

© Privat

Aiming high – not just in research. Felix Hormann is also exploring new perspecitves beyond the Danish laboratories.

© Privat

Are there any differences between the German and Danish research mindsets?

Hormann: The first few days at the institute felt quite different from those in Dortmund. Because it’s winter and it gets dark in Copenhagen as early as three p.m., many people don’t start work until nine in the morning. This way, they can at least make use of a little daylight before the day begins. After eight hours of work, most researchers leave; only a few stay longer, for example to run one more experiment. The idea is to use the time on site as efficiently as possible and then find time to clear your head afterwards.

My Danish colleagues find social factors very important. For example, we eat lunch together and set time aside for a coffee break between meetings. Overall, everything feels a bit more relaxed compared to Germany, but we are still very productive.

There are also many opportunities to try out the various devices in the laboratory. This may be partly because the institute is part of a university. Hierarchies are very flat, and you are free to look at other projects. This fosters many new ideas and joint experiments.

What are you learning from your time in Copenhagen?

Hormann: In Copenhagen, I’ve learnt more about the analysis of hormones and their influence on health than ever before. This was simply by being allowed to participate in the group seminars and lectures held by our entire research department. To discover things beyond your own horizon, you have to keep asking yourself: What are others actually doing? Here in the Danish research group, the focus is on other molecules – hormones and drugs – and yet I still gained new insights into possible approaches to my own research. I came up with new ideas for topics to explore in my future research, too. Networking is very important. Having the phone numbers of other researchers outside your immediate environment is helpful, because you can ask them, 'How would you do that?'

Is there anything that you would you like to contribute at ISAS after you return?

Hormann: In Copenhagen, I can build on existing guidelines and a substantial amount of preparatory work. My goal is to transition from working with drugs to working with lipids. One major advantage is that the analytical equipment at ISAS is very similar to what we have here. This means that I can easily transfer the protocols I develop here to our research at ISAS. This will help us create a SOP, a standard operating procedure, for our research questions in Dortmund. Apart from that, I’d also welcome the obligatory coffee break during our group meetings — it's a nice tradition! (laughs)

What advice would you give to other doctoral students who are considering a research stay abroad?

Hormann: In any case, talking to people who have already conducted research abroad is helpful. Many people in academia are open about their experiences. It’s also important to reflect on your own working methods and be open to new ideas. Building contacts, including the ones from abroad, is very valuable.

I applied for several scholarships and would advise against giving up if you don't succeed immediately. It may just be bad luck, and it doesn't necessarily mean that your research idea is flawed – often, there simply aren't enough places available. As doctoral students, we’re enrolled at universities, which is how I ultimately obtained my ERASMUS+ grant. I’m also fortunate to have aid from ISAS.

MALDI & DESI

In matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation (MALDI), researchers embed the molecules from a sample in a matrix. The matrix molecules absorb the laser light, which leads to the ionisation of the target molecules (analytes).

Desorption electrospray ionisation (DESI), on the other hand, works with a fine solvent spray. The electrically charged mist hits the sample surface. The applied solvent film extracts analytes from the sample surface. The secondary solvent droplets from the solvent film then lead to the ionisation of the molecules.

Both ionisation techniques allow subsequent analysis of the molecules using mass spectrometry.

(The interview was conducted by Elai Arts.)